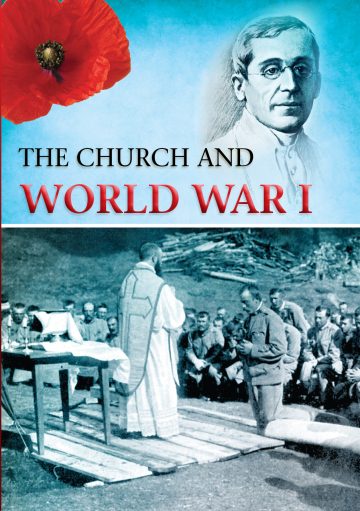

This blog is extracted from Stories of the Great War, compiled in 1915 by Eileen Boland, who was married to CTS’s General Secretary.

It is some consolation that war, with all its horrors, is lightened by the instances of devotion and sacrifice which always emerge from an otherwise tragic and terrible record. The war now being waged has already supplied an abundance of such material, gratifying not only to Catholics, who note the heroism of priests and nuns, and the religious revival in France, with special pleasure, but also to those “other sheep” of the Christian flock who have written and spoken with so much sympathy of these things. Out of this abundance the following pages have been compiled; they relate some of the many stories which throw into vivid light the power of Faith to serve the cause of Fatherland.

“Died Hand in Hand.”

An unnamed priest is the central figure in this story from the Daily Chronicle of October 31st:—

“In the hall of a great railway terminus in Paris a number of wounded were laid out on the straw waiting to be taken to a hospital. Eight of them were very badly hurt, and some of them were evidently not long for this world.

“One of them seemed to be very uneasy. A nurse went up to him and offered to rearrange his bandages. His reply was, ‘I want a confessor very badly.’

“ ‘Is there a priest here?’ asked the nurse.

“Just then another soldier lying mortally wounded plucked the nurse by the sleeve. ‘Madame,’ he said, ‘I am a priest; I can give him absolution. Carry me to him.’

“The nurse hesitated. The soldier was suffering from the effects of a horrible shell-wound, and the least movement gave him excruciating pain. But again the feeble voice quietly said, ‘You are of the Faith, and you know the price of a soul. What is one more hour of life compared with that?’ And the soldier raised himself by a supreme effort to go to the side of his comrade.

“But the effort was in vain. He had to be carried. The confession did not take long, and the strength of the soldier-priest was ebbing rapidly away. When the time came to give the absolution he made a sign to the nurse. ‘Help me to give the sign,’ he said.

“The nurse held up his arm while this was being done. Death followed quickly for the soldier-priest and his penitent. They died hand in hand, while the nurse and the ambulance men fell on their knees on each side of them.”

The Heroine of Gerbéviller.

But the most famous nun at the present time in France is Soeur Julie of Gerbéviller. Gerbéviller itself has been twice burnt, twice bombarded, and for a fortnight occupied by the Germans. Throughout all Soeur Julie remained at her post as superior of the hospital and has earned for herself a foremost place in the annals of the war. “A month ago,” says the Belfort correspondent of the Times (September 22nd), “Gerbéviller had 1,600 inhabitants and consisted of 463 houses. To-day there are six left. The rest are nothing but bare, roofless walls, blackened and desolate, gaping holes which were once windows, piles of ruins. Like Jerusalem of ancient times, the town has been reduced to a heap. The Angel of Death has passed over it, and as a habitation for men it exists no longer. Only at one place, right on the outskirts near the station, there are a few traces of human life in the form of wounded soldiers and inhabitants searching in vain for the sites of their houses; and among them an angel of charity and devotion, a solitary nun, Sister Julie, who throughout the occupation by the enemy and the bombardment remained faithfully at her post, healing and encouraging the wounded and the inhabitants. And in the rest of the town, among the ruins of the church and in the houses, even in the streets, a frightful silence.”

Saving the Blessed Sacrament.

On entering Gerbéviller, the Germans at once began to pillage the church. They attempted, by firing shots at the lock, to break open the tabernacle, but being unsuccessful, they left the church. Soeur Julie succeeded where they had failed, forcing open the lock by means of a bayonet, which had been left in the sanctuary. She found the sacred vessels overturned and pierced by bullets. Collecting the scattered Particles, she brought away the ciborium and hid it in her dispensary cupboard. Later, fearing discovery and sacrilege, she consumed the Hosts. Meanwhile the town had been fired, and Soeur Julie and the three sisters under her began to fear for the wounded in their charge. “I told the Germans,” she said, “that I could not allow them to kill my wounded. They insisted on going all over the hospital, and then they agreed to leave it alone. But I had to protest again, as they wanted to set fire to the rest of the street, and that would probably have meant the destruction of the hospital as well.” Eventually Soeur Julie had the German wounded as well as the French to look after—“a hard trial to Christian charity,” she says, “but we did it.” With the return of the French to Gerbéviller the wounded have been removed, and the nuns, converting their hospital into a bakehouse, still serve their fellow-citizens by baking bread.

Writing at the end of September, a Times correspondent visiting the town says: “I saw practically only two things that were whole. One was a stone crucifix, standing by itself at a point where two streets meet, the other the figure of the Virgin with the Child Christ in her arms, looking from her place above the altar down the shattered nave and through the burnt and broken door of one of the churches—and around and above her on every side this abomination of desolation that the German soldiery have left behind them.”

On November 29th Soeur Julie was presented with the Legion of Honour, by the President of the Republic himself, “for having by her presence of mind and firmness defended the hospital and provided for the subsistence of the wounded and the inhabitants during the bombardment.”

How Father Finn Died.

The first British chaplain to fall at the post of duty was Father Finn, of the Middlesbrough diocese, whose heroic death in the Dardanelles operations is thus recorded in the Daily News (June 7th):—

“The losses sustained by the Dublins and King’s Own Scottish Borderers in the Dardanelles have been greatly felt by the many friends of these two regiments in Cairo, where they did garrison duty some five or six years ago, but perhaps no death has been more keenly felt than that of Father Finn, the Roman Catholic chaplain, who was so well liked in English circles here.

“Father Finn was one of the first to give his life in the landing at Sedd-ul-Bahr. In answer to the appeals that were made to him not to leave the ship, he replied, ‘A priest’s place is beside the dying soldier,’ whereupon he stepped on to the gangway, immediately receiving a bullet through the chest. Undeterred, he made his way across the lighters, receiving another bullet in the thigh, and still another in the leg. By the time he reached the beach he was literally riddled with bullets, but in spite of the great pain he must have been suffering he heroically went about his duties, giving consolation to

the dying troops. It was while he was in the act of attending to the spiritual requirements of one of his men that the priest’s head was shattered by shrapnel.”

A noble sense of duty; and a fine end. May he rest in peace!

The Rosary.

The following is surely a touching proof of the piety of the French soldiers in the firing line, as well as of the old saw that necessity is the mother of invention. It is taken from a letter by the Abbé Jarraud, a professor at the school of Notre Dame at Issoudun, who has been for four months with the ambulance near the Grand Couronné of Nancy: “At the Presbytery of Varangéville I saw and venerated a rosary made of string, which was made in the trenches by a young soldier of the —— Regiment of the Line, the knots nicely spaced, representing exactly the Pater and Ave beads. This edifying rosary is nearly worn out, for it has seen much service every day of the defence of Couronné. ‘All the men of the section passed it on from one to another to say a Hail Mary,’ said the brave soldier, very simply, who came to the curé to ask in exchange for it a strong rosary to use on the Northern frontier” (Tablet, February 13th).

“A glowing tribute to the piety of the Breton soldiers has been written by one of the chaplains to the Archbishop of Rennes. He tells how they flock to the churches and to the sacraments and say the Rosary together in the trenches. By way of illustration he describes the following little incident which happened in the trenches: The commanding officer of the neighbouring village one day saw one of the soldiers in the trenches saying his Rosary. ‘Do you say it because you are afraid?’ he asked. ‘No, mon Colonel,’ replied the soldier, ‘but because it helps me.’ ‘That’s right,’ said the colonel; ‘let’s say it

together.’ And with this he took out his beads and began to say them with the soldier. The example was infectious; one after another the men did the same, and soon the whole trench was saying the Rosary together” (Cork Examiner, May 15th).

A Christmas Mass.

The following picture of a midnight Mass, celebrated in the war zone to usher in the Christmas of 1914, is taken from the Month (June 1915). It is a French Jesuit who writes:—

“I arranged with our Colonel to say a midnight Mass for those who could get out of the trenches. We fixed on a hamlet well to the front, deserted by its inhabitants and shelled to pieces. Soon the men returning from the trenches appeared, and they could hardly believe their ears when I told them they should have Mass. At once confessions began, one in a cave, another in a room open to all the winds, another in the road. The Colonel took me to the room where the Mass was to be said, when word came that a German attack was expected, and many of the soldiers would have to return at once. I consoled them by promising to bring them Holy Communion afterwards. At midnight I began; there were a few artificial flowers on my altar found by a soldier in a house close by. We could not sing; indeed had to take great care to make no noise at all, so close were we to the enemy; all who were present had their arms with them ready to leave at the sound of alarm.

After the Mass I took the remaining Hosts, but was unable to carry them into the trenches on account of the expected attack. So I clasped the Blessed Sacrament to my breast and lay down on some straw in a cave, by the side of some officers. It was Christmas night, and the Child Jesus lay on the straw of Bethlehem; nothing could happen to us that night at least. And so I fell asleep, meditating upon Bethlehem, and thanking Him for this midnight Mass that had had no music but the thundering of the guns. At six o’clock I was on foot again towards the nearest village, to say my second and third Mass.”