Marie-Bernarde Soubirous was born in Lourdes on 7th January 1844. She was the first-born of parents, François and Louise. She was baptised two days later, soon acquiring the familiar name of Bernadette. At the time family circumstances were auspicious. Her parents were the de facto inheritors of her maternal grandparents’ flour mill, Boly Mill, a successful and prosperous business. As the only child amongst adults she was loved and no doubt spoiled by the extended family that lived there, but unusually, whilst still a baby, she was put out to a wet nurse following an accident which prevented her mother being able to continue breast feeding. It was not until she was two that she returned home again to be greeted by her new baby sister, Marie-Antoinette (familiarly known as Toinette). By this time the extended family living at Boly Mill was in argument and disarray and in the process of going their separate ways, leaving, in 1848, Bernadette’s parents with the prospect of running the mill without the advice, skilled help and motivation previously given by the close family.

Family difficulties

Bernadette’s father, François, is described as being a peaceful and humble man, a good and reliable worker under an employer’s supervision, but with little business acumen. These traits soon took their toll, and the business failed, ironically through their over-generosity, of which advantage was soon taken, and eventually lack of money to buy new machinery necessary to keep the business competitive. The Soubirous family were forced to move from the mill in 1854, under the cloud of debt and scorn. By this time their own family had grown, and of the nine children that the Soubirous were eventually to have, six had been born, of which the survivors were Bernadette, Toinette, their brother Jean-Marie, aged four, and a new born baby, Justin.

In a series of moves from one wretched lodging to another, and another failed business venture, the Soubirous finally ended up in the famine year of 1857 in the now celebrated cachot, the former prison cell, judged to be too unhygienic – even by nineteenth century standards – to be used for this purpose, and being underneath the house of one of Louise’s cousins. In this stinking, cramped, vermin ridden cell, overlooking a cess pit and barely twelve feet by fourteen, the family of six took up residence with their meagre possessions, and continued the grim, unremitting grind for survival.

Despite these privations the family were generally remembered as being loving and affectionate, and Louise was described by one of her relatives as being, “a good Christian, kind natured and hard working. She brought up her children well”. However, probably in keeping with the times, love was tempered by discipline and the cane, as in a comment from one of Louise’s sisters, “their mother brought them up well, without sparing the rod; and I also used a cane to keep my children in line”. They were also essentially a devout family, judging from reports of neighbours that they could be heard saying their prayers together every evening. There was, however, a darker side, as François in particular had gained the reputation of becoming a heavy drinker and a bit of a layabout, and Louise was also reported as succumbing to alcoholic bouts. These activities, should be judged, though, within the strata of society in which they now found themselves, where over-indulgence of alcohol was seen as typical rather than outrageous.

So it was against these destitute and humiliating circumstances that François and Louise sought what work they could to support their family. François, blinded in one eye in an accident at Boly Mill, found what casual jobbing work that was available, although one of the relatives commented that, “he did not exert himself for every type of work”. He also suffered the ignominy in 1857 of being branded a thief. He was suspected of stealing a bag of flour, and then accused of the theft of a plank of unexplained wood in his house. He was jailed for a few days, but then released for lack of evidence to prosecute. Nonetheless the ‘mud stuck’. Louise worked in laundries, laboured in the fields and scavenged for wood in the nearby forests. Set against this background of family deprivation and humiliation was economic depression, famine and disease in the area.

Childhood days

Reminiscences of Bernadette during this period give a picture of a ‘dreamy and careless child’, but also kind-natured and conscientious. Physically she was tiny, even by the standards of the short statured people of the region. She was seen as a resolute little person, gamely lugging her baby brother around on her hip, and her face was described as, “round and pretty with beautiful soft eyes”. Certainly our own image from the pictures we see of her depict a reserved, calm person, seemingly always striking a slightly defensive pose with a challenging look, but one softened with liquid eyes, a neat nose and a soft, full mouth. She was clean, tidily dressed and neat, and despite her impoverishment, maintained a dignified way of conducting herself in an echo of how she would have done in better circumstances.

But even in better circumstances she would have been in poor health which the conditions of poverty only served to exacerbate. She developed asthma at an early age, but she did survive to adulthood five of her brothers and sisters, four who died in infancy, and her brother, Justin, dying aged 10. In Toinette’s words, Bernadette, “had a bad chest, she ate very little”. It says something for God’s plan for her that against all the statistical odds for children of her age in that region, aged eleven, she survived cholera. But this left her even more weak and sickly; the violent purging had ruined her digestive system, and thereafter she had difficulty in digesting the staple foods of the region, often vomiting after eating. All her life she bore, and wore, the mantle of the sick, a sure presaging of the healing mission of Lourdes. In fact her philosophy on life in those days was summed up when she commented at a later stage, “When one desires nothing, one will always have what one needs”.

The family’s impoverished state made her the natural ‘second mother’ to tend the young ones whilst her mother was out working. She also worked as an occasional waitress. This undertaking of these familial duties in her earlier years effectively deprived her of any real chance of a sound education, and not only this, it also meant that her younger siblings, without family duties, went on to receive some form of education. Much evidence suggests that she was not an intelligent girl given to swift academic learning or retention of facts, she in fact had a poor memory.

This lack of formal education also had a knock-on effect in her spiritual life and development. Her family duties also kept her away from the catechism classes so vital to preparing for First Holy Communion, and her lack of general education meant that ‘catch up’ was virtually impossible. This first encounter with the Sacrament was seen as an important threshold to be crossed in a child’s life – leading to acceptance into the adult world. Again Bernadette suffered the disappointment of seeing her younger sister, Toinette, going to the communion rail, while she looked on. What is certain though, through the words of her aunt, was that, “the rosary served as her school book”. She would, of course, have known the common prayers of the day, so although lacking in formal religious education she certainly had experience of her Catholic practice, and particularly of the significance of Our Lady.

Away from home

In 1857 another ironic twist came to Bernadette’s life. Madame Lagues, her former wet nurse, who had kept in touch with the Soubirous family, asked that Bernadette, now aged thirteen, came and lived and worked in her household in Bartres, an hour’s walk from Lourdes. This was potentially a godsend to the Soubirous family having one less mouth to feed, particularly now that the other children were largely self-sufficient. In fact, the Soubirous offered the services of their other children too, but Mme Lagues specifically wanted Bernadette.

Bernadette’s tasks at Bartres were looking after the five Lagues children, a job she was well equipped for, and tending the sheep, one which she was not, but it was not a particularly onerous one. It was during this short sojourn that many of the inaccurate depictions of Bernadette as mystic shepherdess grew; stories of her flock of sheep crossing the parted waters of a swollen stream, or not getting wet from the rain. Bernadette emphatically denied these stories, much to the disappointment of her admiring wishful thinkers. The reality of life at Bartres was one of austerity and harshness. For the Lagues were the very opposite to the Soubirous in the peasant milieu. They were frugal, hardworking, very pious, and with their family small-holding had reaped the benefits. Mme Lagues’ attempts at teaching Bernadette the catechism ended in her frustration at the girl’s lack of learning ability. There seemed to be an alternating display of love/hate for Bernadette; some witnesses describe her love for the child, others that she hated and mistreated her. In Bernadette’s words, “my wet nurse was not always kind”.

Simple spirituality

Although her mother had remarked that from a very early age Bernadette showed “a marked inclination towards piety” there was nothing particular during the Bartres period that seemed to mark her out for sainthood. On her deathbed Bernadette was asked whether she had recited the rosary in the fields at Bartres, “I don’t remember that”, she replied. She liked to construct little altars and shrines in May, but that was local practice and nothing unusual. Was she pious? “Oh! Like everyone else”, was one of the Lagues girl’s reply. But – there was undoubtedly something there, not as explicit and overt as the Fatima children, but something. It is summed up by René Laurentin as a, “spirituality hidden in simplicity… the holiness of Bernadette lay outside the bounds of any spiritual instruction… Bernadette was a stranger to all reflective awareness. She lived a spiritual night. To put it plainly and simply it was the night of the pauvres, the ‘poor little ones’ who awaited the Good News while carrying out the ‘will of God’ and enduring what he permits” (Bernadette of Lourdes), the last phrase a sentiment expressed by Bernadette herself at the time.

Bernadette herself instigated the end to her time at Bartres. She was determined to return to Lourdes to prepare herself for her First Holy Communion. She returned to the cachot early in 1858. Whilst the family was still no better off materially, she finally started receiving a regular education, and more importantly to her, formal instruction in catechism with Abbé Pomian, vicar of Lourdes. Whatever thoughts her parents, or Mme Lagues, had about Bernadette returning to Bartres after she had received her First Holy Communion can only be speculative, as the events which started on 11th February, two weeks after she had returned home, were dramatically to change the course of her life, that of her family’s, and that of the small town of Lourdes.

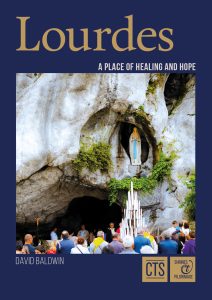

This blog is extracted from our book Lourdes: A Place of Healing and Hope, which tells the story of Bernadette Soubirous, while also serving as a spiritual and practical guide for pilgrims to the best-known Marian shrine and its message of hope, healing, intercession and conversion.

This blog is extracted from our book Lourdes: A Place of Healing and Hope, which tells the story of Bernadette Soubirous, while also serving as a spiritual and practical guide for pilgrims to the best-known Marian shrine and its message of hope, healing, intercession and conversion.

To learn more about Lourdes and St Bernadette, order your copy of Lourdes: A Place of Healing and Hope today.