And Mary said:

‘My soul proclaims the greatness of the Lord

and my spirit exults in God my saviour;

because he has looked upon his lowly handmaid.

Yes, from this day forward all generations will call me blessed,

for the Almighty has done great things for me.

Holy is his name,

and his mercy reaches from age to age for those who fear him.

he has shown the power of his arm,

he has routed the proud of heart.

He has pulled down princes from their thrones and exalted the lowly.

The hungry he has filled with good things, the rich sent empty away.

He has come to the help of Israel his servant, mindful of his mercy

-according to the promise he made to our ancestors-

of his mercy to Abraham and to his descendants for ever.(Luke 1:46-55)

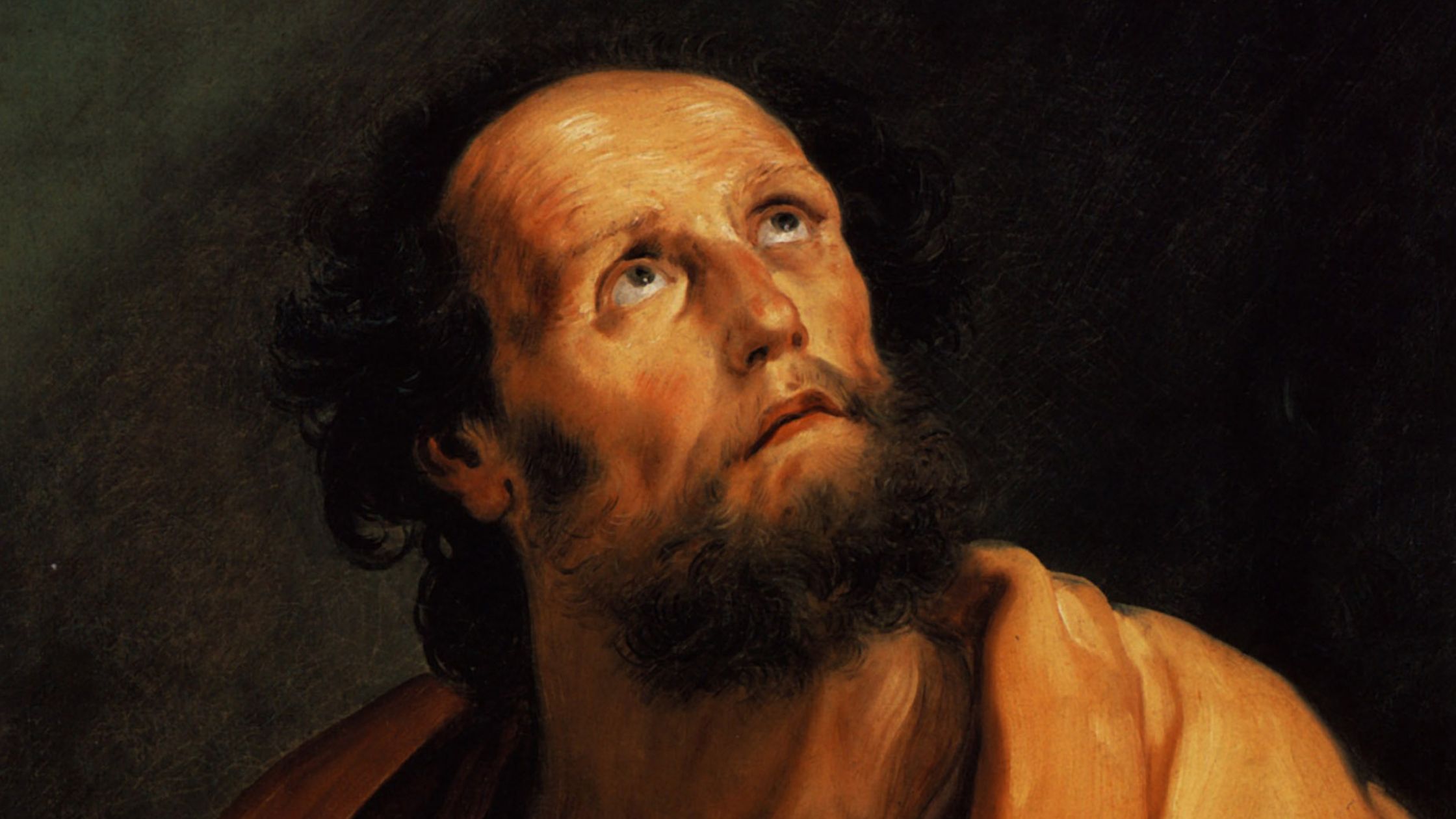

St Luke the Evangelist – Feast: 18th October

Today’s saint is written by Fr Nicholas Schofield in Saints of the Roman Calendar.

St Luke (first century) was a Greek, possibly from Antioch, who trained as a doctor. He converted to Christianity, became a disciple of St Paul and wrote both a Gospel and the Acts of the Apostles. His vivid descriptions of the childhood of Jesus has led some to believe that he was close to the Blessed Virgin Mary. He is believed to have died in his old age, and may have been martyred; he is patron of doctors and artists.

Collect

Lord God, who chose Saint Luke to reveal by his preaching and writings the mystery of your love for the poor, grant that those who already glory in your name may persevere as one heart and one soul and that all nations may merit to see your salvation. Through our Lord Jesus Christ, your Son, who lives and reigns with you in the unity of the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever.

Collecta (Latin)

Domine Deus, qui beatum Lucam elegisti, ut prædicatione et scriptis mysterium tuæ in pauperes dilectionis revelaret, concede, ut, qui tuo iam nomine gloriantur, cor unum et anima una esse perseverent, et omnes gentes tuam mereantur videre salutem. Per Dominum nostrum Iesum Christum Filium tuum, qui tecum vivit et regnat in unitate Spiritus Sancti, Deus, per omnia sæcula sæculorum.

St Luke: the Writer & His Gospel

Written by Dom Henry Wansbrough OSB in our book Gospel According to Luke.

In the ancient world around the time of Jesus there was a high standard of culture in the Roman Empire (allied to, and in some sense built on, serious physical cruelty). Literature of all kinds was widely diffused and widely read, including short treatises on such subjects as navigation, arms manufacture, medicine, as well as romantic novels. The first few verses of Luke’s gospel set it firmly among such works, for biographies of religious figures are included among these works. his Greek style, more sophisticated than Mark’s rough language, puts him at home in this grander world. His vocabulary is wide and his use of the language exploits the flexibility of its syntax. Luke’s delightful skill as a story-teller (little scenes with entry, dialogue and exit; parables with lively and complex characters, who do the right thing for the wrong reason, who vividly express their joys and worries) would have made his two volumes highly acceptable among such literature. he is a master at conveying a theological message through visual scenes such as the Annunciation (1:26-38) or the Journey to Emmaus (24:13-35), a talent which makes gripping reading in his second volume, the Acts of the Apostles, the story of the earliest Christian communities.

Luke moves easily in this cosmopolitan world. He situates Jesus’ birth and the beginning of his ministry in the context of world history by the roll-call of world rulers of the time (2:1-3; 3:1-2). he uses larger sums of money than Mark, silver instead of copper (9:3 contrasting with Mk 6:8), and imagery from the business world, banking and rates of interest, debtors, creditors, swindlers, in a way which would have been unintelligible to Mark’s audience. Not surprisingly in this context Luke is eager to show that Christianity is no threat to the stability of the Roman world; accordingly he stresses that Pilate had nothing against Jesus, but three times declares him innocent (23:4, 14, 22), tries to shift the responsibility by handing Jesus over to Herod, and finally, instead of condemning him, merely hands him over to the Jews (23:25).

Another indication of Luke’s cosmopolitan background is his attention to women, who played a more open and forceful part in the Greco-Roman than in the Semitic world. So Luke indicates that Jesus was accompanied and supported in his proclamation by a group of women as well as the Twelve (8:2-3). He regularly pairs women with men (Zechariah and Mary – each receives an annunciation, 1:5, 27; Simeon and Anna, 2:25, 36; the owners of the lost sheep and of the lost coin, 15:4-10), showing them as the beneficiaries of miracles no less than men (the Widow of Nain and Jairus). Mary is the first and prime example of the disciple, in that she first hears the word of God and keeps it (1:38; 8:21; 11:28).

Luke, the Critic of Worldliness

At the same time, however, Luke does not scruple to show his criticism of this richer world, pointing out the dangers of wealth (the parable of the Rich Fool, 12:16-20, or of the Rich Man and Lazarus, 16:19-31), the need to use wealth and position for good ends (14:7-11; 16:8), and insisting that salvation comes first to the poor (hireling shepherds, 2:8, compare 7:21-22), the unfortunate (the barren couple, Zechariah and Elizabeth) and the outcast (lepers, sinners, tax-collectors). While Matthew’s eight Beatitudes (Mt 5:3-10) concentrate on attitudes of spirit, the poor in heart who hunger for righteousness, Luke’s four Beatitudes (Lk 6:20-23) bless with stark realism those who are actually poor and hungry, and are balanced with four Woes on the rich and comfortable. It is perhaps through the consciousness of the dangers of such a lifestyle that Jesus ceaselessly proclaims the need for conversion and repentance. Acknowledgement of sin is an essential prerequisite of being called to follow Jesus. This is the case with Peter (5:8), the Woman who was a Sinner (7:36-50), Zacchaeus (19:1-10), the Good Thief (23:40-43), and the crowds at the Crucifixion (23:48). Conversion, a complete reversal of standards and way of life is demanded from beginning to end of the gospel (3:7-13; 5:32; 10:13; 24:47). Correspondingly, the welcome awaiting repentance and the joy in heaven at the conversion of a sinner is repeatedly illustrated (15:1-32).

A Gospel for the Gentiles

Consonant with his own hellenistic, non-Jewish position, Luke shows Jesus from the first envisaging the gentiles in his mission, whose outlines are set out at the very beginning of Jesus’ ministry, in the great programmatic speech in the synagogue at Nazareth (4:16-30). perhaps especially favoured are the Samaritans, those hated neighbours of the Jews, as the prime example of response to the values of the gospel in the persons of the Good Samaritan (10:29-37) and the Samaritan leper (17:11-19). It might even seem that the Jews themselves are excluded from the salvation originally promised to them. In the Acts of the Apostles there is almost uniform opposition from the Jews to the Christian message, and three times Paul is forced to turn from the Jews to the gentiles (Acts 13:46-47; 17:5-7; 28:25-28). Luke, however, leaves no doubt that the ‘light to enlighten the gentiles’, as Simeon says, is also ‘the glory of your people Israel (2:32), for the stories of Jesus’ infancy are suffused with the atmosphere of devotion to the Law and the humble piety of the poor of Israel. Nowhere is this clearer than in the three canticles of Zechariah, Mary and Simeon, which have been adopted into the Church’s liturgy (1:46-55, 67-79; 2:29-32). They could almost form part of the Old Testament. In fact the opposition to Jesus comes overwhelmingly from the leaders of the Jews, while the ordinary people almost uniformly support him (23:10, 27).

The whole gospel is centred on Jerusalem, for there it begins and ends. The second half of the gospel consists of Jesus’ resolute journey to his death at Jerusalem (9:51-19:27). Jesus’ own devotion to the Holy City is shown by his laments over it at both beginning and end of his ministry there (19:41-44; 23:28-32); during his time in Jerusalem he teaches daily in the Temple (19:47). The appearances of the Risen Christ are in Jerusalem rather than Galilee (24:13-43), and after the Ascension from the Mount of olives outside Jerusalem (24:50-53), the gospel will spread from Jerusalem to all nations (Acts 1:8).

The Jesus of Luke’s Gospel

Jesus himself is presented as a prophet after the model of the Old Testament prophets, though right from the beginning the elaborate contrast with his cousin John the Baptist shows that he is greater than the last and greatest of the prophets. At Nazareth he takes Elijah and Elisha as his models in his mission to the gentiles. By the people of Nain he is hailed as a prophet (7:16). The Transfiguration shows him as a prophet discussing his approaching death with the other great prophets, Moses and Elijah (9:30-31). like all the prophets he must die in Jerusalem (13:33), and his Ascension to heaven is modelled on the ascension of Elijah in a fiery chariot (2 kings 2:11). Like the ancient prophets Jesus is filled with the Spirit (4:1, 14, 18), thus preparing the way for the Spirit who will guide every movement of the early church. As the mission of the church begins with the descent of the Spirit at Pentecost (Acts 2:1-4), so the mission of Jesus himself begins with the descent of the Spirit at his baptism (Lk 3:22). He is fully conscious both of his destiny, particularly to fulfil the scriptures, and of the destiny of his followers, for whom he is the primary role-model. Especially in the great journey up to Jerusalem they are carefully instructed in their duties, in the need for perseverance under persecution, for poverty and for prayer. At the Agony on the Mount of olives Jesus prepares them by giving them a noble and dignified example of fervent prayer in time of trial (‘pray that you enter not into temptation’, 22:40, 46), for prayer is a special feature of Jesus’ life, especially at its turning-points (3:21;11:1; 22:41). This same gentle dignity characterises also the scene of the crucifixion: it is a display of conversion and repentance, where Jesus continues his mission of forgiveness until finally he consciously yields up his spirit to his Father (23:34, 43, 46).

Who was Luke?

The presentation, style and emphases of the Acts of the Apostles leave no doubt that both volumes stem from the same hand. Some passages in the second volume present the author as sharing in paul’s missionary journeys; he is certainly very conversant with the cities of the eastern mediterranean and their constitutions. Paul’s letter to Philemon (v. 24) mentions a certain Luke as being with him, and Colossians 4:14 describes luke as a doctor. The name was common in the roman world, but traditionally the two volumes are ascribed to the authorship of this Luke the doctor. In writing his gospel luke certainly used that of Mark. For his extensive range of the teachings of Jesus, scholars are divided whether he used the same collection of the ‘Sayings of Jesus’ (now lost) as Matthew, or whether he drew directly on Matthew’s own gospel. Such decisions could well affect the dating of the gospel, so that it is difficult to be more precise than to say that the gospel was written towards the end of the first century.

Reading Luke

In reading Luke in a comfortable world be aware of Jesus’ call to conversion and to his absolute demands. At the same time wonder at his delicacy, gentleness and love for the sinner. In reading the parables especially (where Luke is composing more freely) enjoy the wit and sparkle of Luke’s imaginative writing. He was writing in a world where many such works existed, but for him Jesus was the climax of history, to whom all previous history pointed, and with whom all later history began.

https://www.ctsbooks.org/product/gospel-according-to-luke/

https://www.ctsbooks.org/product/acts-of-the-apostles/

Want the Saint of the Day sent straight to your inbox? Sign up for our Saint of the Day emails and we’ll help you get to know the saints by sending you an email on the feast or memorial of every major saint, and on the optional memorial of select other saints. Opt out at any time.