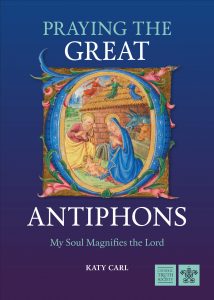

In the final days of Advent, the Church recites the Great O Antiphons at Vespers each evening. In this blog extracted from Praying the Great O Antiphons, Katy Carl reflects on the seventh of these O Antiphons: O Emmanuel.

Gospel Acclamation:

Emmanuel, our king and lawgiver, come and save us, Lord our God.

Magnificat Antiphon:

O Emmanuel, you are our king and judge, the One whom the peoples await and their Saviour.

O come and save us, Lord our God.

Reflection on O Emmanuel

This antiphon speaks what is, in the end, each human heart’s deepest desire: to have God with it, to be with God, to be in God, and to know God’s indwelling. This is precisely what the name Emmanuel means: God with us. To accomplish this being with us, Jesus came to earth and inhabited a human body. For this reason “the Word became flesh and dwelt among us” (John 1:14). The story of our redemption springs from no other root than love. Even more than we long to be embraced, ennobled, transformed, God longs to embrace and ennoble and transform us.

In human terms, this makes either all the sense in the world or, perhaps, absolutely no sense at all. Why would the Creator of all things, perfectly happy in himself and with no need of human life or a created world, not only decide to create souls inside bodies, but to take on this embodied, ensouled creaturehood for himself? If what God wants is souls, what purpose is served by all these querulous, problematic, high-maintenance bodies we carry around the world with us? Would we have wanted to become incarnate, if we had been God? The idea of substitutionary atonement is next to impossible to wrap our minds around, because it lies outside the logic of human psychology unaided by grace. Even under the influence of grace, how many of us would ever do it, knowing that to do it completely would mean indescribable suffering?

God, fortunately for us, does not have the kind of cold clockwork heart we humans often imagine for him – an assumption that has more to do with the kind of heart we tend to carry around inside ourselves than it does with the heart of God. Instead, his heart yearns towards us. The more we suffer, the closer to us he longs to be. The more we suffer, the more he is with us, in a mysterious yet real way. The saints describe this experience, but it is not an experience restricted to saints alone. It is there for the asking, for all of us who know what it is to be “mourning and weeping in this vale of tears.” “For one will scarcely die for a righteous person – though perhaps for a good person one would dare even to die, but God shows his love for us in that while we were still sinners, Christ died for us” (Rom 5:6-8).

If we believe what Caryll Houselander saw in her mystical vision of Christ – alive, at work, asleep, or dead in every single human soul – we also see that this life of Christ is, in one sense, always as close as our own hearts. In another sense, though, we are not one with Christ until we receive the Sacraments. Until then, we lack access to that deeper friendship with Christ in which he is ‘another self ’ to us. To put this another way, Christ desires a certain reciprocity with us. Our concerns are always his, but the circle is not complete until we make his concerns ours. When we step forward into this friendship, always first moved by grace, he then becomes our “king and lawgiver” in a way that parallels the presence of God given to the first humans, who walked ‘with God’ in Eden. He then dwells directly in our hearts, pulling us ever more completely into the life of the Trinity. He then guides and leads us from within, in close and compassionate conversation with us. This conversation, which is what prayer consists of, begins now and extends into eternity. It proves the reality of the bold statement made by St Catherine of Siena: that Jesus is like a ‘bridge’ connecting heaven and earth, by which “the earth of your humanity is joined to the greatness of the Deity.”

Prayer and the Sacraments place us on this bridge, a path that, as St Catherine reports, God calls each one of us individually to pursue: “It is not enough, in order that you should have life, that My Son should have made you this bridge, unless you walk thereon.”20 On the bridge that is Christ himself, the bridge that is his Incarnation, Passion, Death, and Resurrection, perennially made present in the holy sacrifice of the Mass, no one walks alone. No one is saved alone; we always need the Church, the one community that is also a communion with Christ, because while he was on earth he united himself to it. When we make God’s concerns our own, we always, inescapably, become concerned with our neighbour’s wellbeing, too. For God is equally concerned with the welfare of every single person – and one reason for so much suffering is that, although God is equally concerned with all, each one of us is mostly concerned with self. Instead of bringing forth what we have in us to bear, we frequently choose to escape into the distractions of comfort, pleasure, or (let’s admit it) self- righteous indignation that those people over there haven’t changed yet. Let us not deceive ourselves. The world, our relationships, our institutions, our environment, will never change until we do. And only God can change us: and he can do this only from within.

How fortunate for us, then, that he became so small: so small, small enough to fit inside Mary’s womb (non horruisti virginis uterum). Smaller than a mustard seed, smaller than faith itself: precisely as small as a blastocyst – a microscopic, pre-embryonic human – allowing himself to quietly implant and to grow. How fortunate for us that he allowed himself to grow, not in a miraculous acceleration of progress, but at precisely the pace that we ourselves grow. Nine months after the Annunciation, how fortunate for us that he was born: as purple and slick, as silky and fragile and fragrant, as wonderful, as terrible, as awe-inspiring, as any couple’s first baby: no more and no less so, to look at him from the outside, than any other newborn. And yet this newborn was God. How fully he ‘commands what he gives and gives what he commands,’ in asking us to ‘love God with all our heart and all our soul and all our strength.’ How easy to love, how completely lovable, he makes himself in this Incarnation: how unthreatening, how gentle, how vulnerable: “O happy fault, o necessary sin of Adam, that merited for us so great a Redeemer.”

And all the while, whether we have never left the path, have wandered away from it for a time, or have only begun to discover it, he loves each one of us as his own, only child. He is always with us, within us, waiting to be welcomed, perhaps waiting to be noticed. He awaits only our openness, our willingness, in order to be born into the world once more.

That image of the infant Christ waiting to be born brings us to one other thing I find in this antiphon, beyond the ideas of impending reunion and restoration: namely, a poetic turn. Often found towards the end of a story or sonnet, this literary device restates or recombines an idea in a way that helps us see it still more clearly. Catholic writer and scholar Randy Boyagoda finds a poetic turn “Halfway through the Hail Mary,” a silence between the two main phrases of the prayer, which he reads as signifying the birth of Christ.22 The poetic turn in the O Antiphons, I suggest, takes place here at their ending and signifies not the actual birth of Christ but the moments just before it: the stage known to every labouring mother as transition.

Anyone who has ever witnessed or experienced labour knows that transition is intense. Instinct takes over, and whatever is deepest in the heart finds itself coming up to the surface. It is a moment marked by one purpose: the child must be born, and the mother must find a way. She must put aside whatever stands in between her current state and the success of her effort. You and I and everyone else reading this page are breathing right now because she succeeded.

The urgency of that moment may often be used as an analogy, but those who have done it know it compares to nothing else. The technical term for the physical process that, quite literally, crowns the endeavour – foetal ejection reflex – does not begin to cover the human experience of giving birth. It is totalising, requiring in that moment all the person has, all she is: all her heart, all her soul, all her strength. Birth, like the story of salvation, is eucatastrophic. Do we feel an intensity like this in our desire to bring Christ into the world anew? If not, what might be standing in between us and that intensity? How might we begin to put that aside, to make room for our Lord in our lives, in our very bodies – giving new meaning to Isaiah’s “In the wilderness prepare the way of the Lord, make straight in the desert a highway for our God” (Isa 40:3)?

“O Emmanuel” captures in compressed form every idea that has been present in the preceding six antiphons. Its brevity suggests that there is not much time left to say what needs to be said. We had better say it now, while we still have breath left! Christmas is almost here: the breathless push into new life is upon us.

Image copyright Fr Lawrence Lew OP.

This blog is extracted from our book Praying the Great O Antiphons. In the final days of Advent, the Church recites the Great O Antiphons at Vespers each evening. Katy Carl contemplates each of these antiphons, drawing on art, literature, and Sacred Scripture to show how they tell the story of Jesus Christ, the Babe of Bethlehem.

This blog is extracted from our book Praying the Great O Antiphons. In the final days of Advent, the Church recites the Great O Antiphons at Vespers each evening. Katy Carl contemplates each of these antiphons, drawing on art, literature, and Sacred Scripture to show how they tell the story of Jesus Christ, the Babe of Bethlehem.

To learn more about the O Antiphons, order your copy of Praying the Great O Antiphons today.