Trials, whether of loneliness, absurdity or death, cause us to lose the peace of mind which we had so long sought and built up in our relationships with others, with things and in the pacification of our own hearts.

In community or in our personal life, we need to discover the reality of that experience, when peace now seems to have totally fled our lives, whether through external conflicts or interior trials that plunge us into the anguish of loneliness, absurdity and meaninglessness, or death.

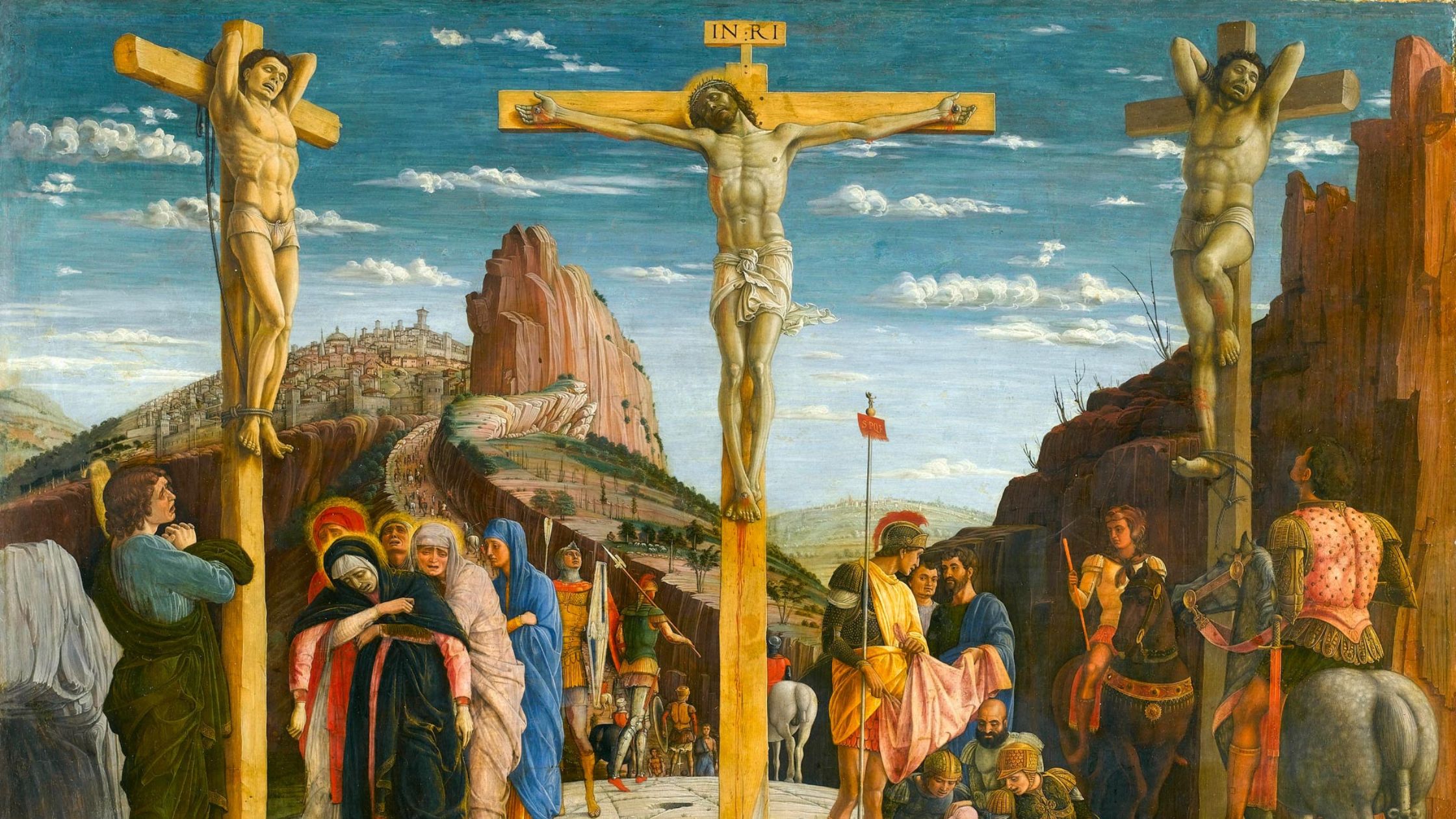

The Wisdom of the Cross

The wisdom of the Cross demands that we avoid false sufferings, those arising from the worsening of our trials which we, consciously or unconsciously, cause ourselves; above all, it demands that we go through the real trial with which following Christ presents us. We will then rediscover peace, but only after the trial.

For that to happen, we need to accept and enter into the trial, whether of loneliness, absurdity or death, without hardening or armouring ourselves against it so as to be unaffected by it; without revolting against it in order to overcome the suffering; without fleeing, being well aware that the trial is within us, and we will encounter it again elsewhere.

It is also good not to over-dramatise it (but we should equally avoid minimising it). Much of the worsening of sufferings and trials arises from our wrong attitudes to them.

We need to be realists. We will not find peace other than in the trial itself, by agreeing to follow Christ on his way of the Cross. That peace will be found redeemed and transfigured by the gift of life beyond death, the fruit of trust and self-abandonment.

For Christ did not make use of the power which was his in his divine nature in order to avoid suffering and save himself from the trial of the Cross. He went to the very end of the loneliness of abandonment.

He experienced to the limit the absurdity of the situation of the condemned innocent, the creator accused by the creature. He went all the way to death, all the way to his last breath. He consented to the trial which was put before him, in trust and abandon, waiting on God alone, to be saved from death, beyond death, by the Resurrection.

In our trials it is good for us to meditate on the Passion of the Lord. It is just when we offer him our crosses, by detaching ourselves from them, and when we take up his Cross, that we discover how much his Cross is carrying us, because it is life-giving and glorious, while ours crush us.

Abandonment

I would like to develop a little more the meaning of this path of self-abandonment which we have to follow in our trials. Three words sum up this attitude of “active abandonment”: welcoming, consenting, offering.

Welcoming

First of all we need to welcome realistically the trial that is set before us, to see it in the full light of day, standing back from it, so as neither to dramatise it nor to hide or minimise any aspect of it. It involves an effort to be lucid about it, so that we can get away from reactions limited to our feelings.

Just to face up to the trial I am asked to live, or the temptation that has seized me, or, again, the precise nature of the order I have received, but which seems to me impossible, already requires a great grace of strength.

For that I need to rid the trial of all the elements which my imagination adds on to it. But the light or lucidity which I must bring to this first stage will impact on my own subjectivity and my attitude in the face of this trial.

I shall need to face up to the revolt I am feeling, the fear which invades me, the sadness which paralyses me, the sorrow which prevents me from thinking or reacting. In short, I will take account of all that goes along with my trial, in my feelings, in my emotions, in my imagination. That is what welcoming the trial realistically means.

But it is good to perform this enlightened acceptance of the trial with a brother or spiritual father who can help me to take the precise measure of the effort it demands, to calm everything which the imagination uselessly adds on to the trial, or to see what element of my trial arises from injured vanity, humiliated pride, deprived feelings… because all that is bad suffering, which I can pacify by pacifying my passions, with God’s grace.

Freedom must grow in me, and freed from the passions I will be in a better state to deal with the objective trial, with the strength that comes from the Cross.

But in the light I will perhaps discover, to my great confusion, that there is no objective trial, that the combat is purely one of the feelings… It is most important to have seen this and realistically to accept my weakness.

So already, in this first stage of light, I will find a great peace.

Consenting

The second stage of this path of abandonment, once the spirit is calm, says St Benedict, is to embrace patience – in other words, to enter into this trial with the sweetness of consent.

Consenting without flight, without armouring ourselves against it, without stiffening up, without rebelling against it. Consenting to the absurdity and meaninglessness which I do not understand, consenting to loneliness of heart, consenting to the sorrow of the little or great death which it has been given me to live.

Consenting also means feeling: feeling in my senses, in my imagination, not rejecting anything out of fear… Embracing harsh circumstances and wounding injustices.

Consenting to be tried for as long as God wishes. Consenting to wait for God and his time, as St Benedict says. Bearing and enduring for the Lord, on account of him. So, as we consent, we will discover the joy of victory, a strength like Mary’s, which supported her at the foot of the Cross, and which is already a sharing in the new life that will flood into us completely at the Resurrection.

What the Lord asks of us, when we are a bit wiped out by the trial, is to believe God, to hope in him, because he is just as Almighty as he is God. To hope, even when we are flat on our faces, incapable of getting up, but to hope with a lively, indestructible hope. In those moments we do not recognise the Cross in the suffering which seems like a monstrous contradiction; it is only afterwards that we come to realise that through that suffering, that temptation, we have become what we are.

Madeleine Delbrêl

Offering

Lastly, we distinguish a third stage in this movement of abandonment to God’s will, though of course, in real life, these three stages form a single leap of the soul. This third stage is that of offering: “For you, on your account, we are condemned to death all day” (Ps 43:23).

This offering, this cry to God from out of the depths of our trial, this opening to what is above, has the power to overturn that attitude of withdrawing into wounded nature, mortified vanity, disappointed pride, deprived sensitivity, and to rediscover an attitude of offering, open to the mystery and not brought up short by the absurd or closed up in loneliness.

This attitude of trust and faith in love is the essence of the spiritual sacrifice which is asked of us. Then we no longer identify ourselves with the trial, the suffering, the temptation. We give ourselves over completely to God in a surge of love. By charity, entrusting himself to God’s help, the monk obeys in what seems impossible to him (see chapter 68 of the Rule).

This is when a new dimension of peace and joy is born, and then begins to grow in the heart of the trial. A new life that is very humble, unforeseen, tender. Joy which endures in the trial. Life flowing from the pierced Heart of Jesus, first-fruits of the Resurrection. Presence of the strength of the Holy Spirit.

This peace which comes from God has no limits. The human peace which we were initially seeking was limited by all sorts of rules, boundaries arising from the place assigned to each thing and to each person, and which, even if they are accepted, are inevitably limiting.

The peace of God is limitless, even to the extent of sometimes frightening us a little. It is so hard for us to detach ourselves from our limits…

May the peace of God which is beyond all understanding guard your hearts and thoughts in Christ Jesus.

This blog is extracted from our book Peace of Heart: According to St Benedict. Learn to welcome peace beyond trials and to see it as a limitless gift from God, through teaching marked by the Spirit of St Benedict.

This blog is extracted from our book Peace of Heart: According to St Benedict. Learn to welcome peace beyond trials and to see it as a limitless gift from God, through teaching marked by the Spirit of St Benedict.

Learn more about how to live peace during trials and support the mission of CTS by ordering your copy of Peace of Heart: According to St Benedict today.